Flora and Fauna that can be found Inhabiting

the Dragon Run Watershed this Month

Archival Index - Scroll down for past articles

June 2024 - Southern Leopard Frog, Slime Molds May 2024 Spatterdock, Common Duckweed Apr.2024 Plantain Pussytoes, Zebra Swallowtail Mar. 2024 Northern Spicebush, Spotted Turtle Feb 2024 Red-Headed Woodpecker, White-Tailed Deer Jan. 2024 Rusty Blackbird, Beaver in Winter Dec. 2023 Frogs, Bald Cypress Nov. 2023 Eastern Grey Squirrel, Bald Cypress Oct. 2023 Carolina Satyr, Poison Ivy Sept. 2023 Fungi Aug. 2023 Raccoons, Water Striders Jul. 2023 Lizard's Tail, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Dragonflies Jun. 2023 Easter Tiger Swallowtail, Pickerelweed, Barred Owl, Ebony Jewelwing May 2023 Beaver, Mayapple, Turtles Apr. 2023 Marbled Salamander, Northern Water snake, Prothonotary Warbler Mar. 2023 Spring Beauty, Wood Duck, Bloodroot Feb. 2023 Christmas Fern, Bald Eagle, Round Lobed Hepatica Jan. 2023 Muskrat, Club mosses Dec. 2022 Northern Flicker, Cranefly Orchid, N. Amer. River Otter Nov. 2022 Swamp Tupelo, Smartweed Caterpillar, Common Persimmon Oct. 2022 White Turtlehead, Fowler's Toad, Winterberry Sept. 2022 Tiger Swallowtail, Horsemint, Great Black Digger Wasp, Beech Blight Aphid

July 2024

Downy Rattlesnake Plantain by Kevin Howe

I bet most people don’t know that Virginia has nearly 70 different species of orchids. True – Virginia has many more species than nearly all other states – Florida has the most with about 106 species but over half (58) of Florida’s are endangered or threatened. Virginia fares better but we still have about 28 taxa that are of special concern – that is to say, they are rare and have some potential for extinction in Virginia.

In the Dragon Run watershed, our Citizen Science group has documented 12 species of orchids including the well-known Pink Lady Slipper, Cypripedium acaule, and a lesser known but abundant orchid, Downy Rattlesnake Plantain, Goodyeara pubescens. Both species occur in every county in Virginia.

The Downy Rattlesnake Plantain is blooming now and will continue for a month or so. They are one of the few orchids in Virginia that are evergreen – their leaves stay green throughout the winter. The leaves are quite distinctive, being a circular basal rosette of oval two-inch-long leaves with white veins (reticulated) – see photos – and the central leaf vein is quite broadly white. It is named because the leaf pattern resembles the white marking of some rattlesnakes (a stretch, I think). The flower spike of tiny dense white-brown flowers arises from this basal rosette. The tiny flowers are fragrant when fresh so, kneel down and take a sniff. FYI – the lawn grass “weed” we call plantain is not at all related but has similar basal rosette. The Downy part of its name comes from tiny “down”-like hairs which cover all parts of the plant.

This orchid is found in both coniferous and deciduous forests and often said it is our most abundant orchid species in eastern North America but often just overlooked. On your next kayak or hike in Dragon Run, have your nature guide point these out – you will be rewarded and never forget them.

This orchid is found in both coniferous and deciduous forests and often said it is our most abundant orchid species in eastern North America but often just overlooked. On your next kayak or hike in Dragon Run, have your nature guide point these out – you will be rewarded and never forget them.

The Whirligig Beetle by Lindsay Fisher, FODR Summer Intern

During the summer, the waters of the Dragon Run are full of unsynchronized swimmers–the Whirligig Beetle. Named for its circular but erratic swimming patterns, it is a type of aquatic beetle from the family Gyrinidae. This family alone has around 700 species worldwide, with 40 species found in the U.S. and Canada. Depending on the species, these beetles range between 1/4 to 3/4 inches in size. In other words, they are slightly smaller than a quarter but oval-shaped with a metallic black or bronze color.

|

Both predators and scavengers, these beetles eat the larvae of other aquatic insects and detect water ripples to find dead or dying insects on the surface. The split eyes of Whirligig Beetles also help them detect prey, which gives them a view of what is happening both above and below the water. Through these adaptations, the Whirligig Beetle helps control other insect populations.

After hibernating underwater during the winter, these beetles are most active in the summer when they gather in big groups to hunt, scavenge, and avoid predation through large numbers. With it being the Olympics season, perhaps these beetles are even training for the swimming and diving categories (just maybe not synchronized swimming).

After hibernating underwater during the winter, these beetles are most active in the summer when they gather in big groups to hunt, scavenge, and avoid predation through large numbers. With it being the Olympics season, perhaps these beetles are even training for the swimming and diving categories (just maybe not synchronized swimming).

June 2024

Southern Leopard Frog by Lindsay Fisher, FODR Summer Intern

Photo by David Yeager

Photo by David Yeager

Exploring the Dragon Run, you might hear one of its residents chuckling. That resident is the Southern Leopard Frog, Lithobates sphenocephalus, also known as the Coastal Plains Leopard Frog, whose call sounds similar to a chuckle. While we may never know what these frogs are laughing about, they are integral to the Dragon Run and other freshwater ecosystems across eastern Virginia. For instance, these frogs serve as an indicator of environmental quality because of their thin, permeable skin. The Southern Leopard Frog also acts as a predator and prey to other species, including the many insects and snakes also found in the watershed. Beyond its call, another distinctive characteristic of this species is the brown or black spots on its back that give it a “leopard” look. The overall color of the Southern Leopard Frog is brown, green, tan, or a combination of these. The species is also identifiable by the two ridges running down its back, known as dorsolateral folds.

|

|

These chuckling, leopard-like frogs live in the Dragon Run year-round but breed between mid-February and early April. Female frogs lay their eggs (up to 3,000!) on submerged vegetation, which provides food and cover for the eventual tadpoles. Depending on the presence of predators, eggs may hatch earlier to increase the likelihood of survival.

Virginia Herpetology Society

|

Though primarily aquatic, adult Southern Leopard Frogs spend more time away from the water during the summer and are primarily nocturnal. During the warm daylight hours, you might spot them in the moist vegetation along the shores of the Dragon Run, where there is plenty of shade and food. On land, these frogs forage for insects, worms, and other small invertebrates. If lucky, they might even happen across a good spot to practice their stand-up comedy routines.

Slime Molds by Kevin Howe

Most of our Swamp Sightings are plants or animals that are easily seen. But with warmer weather and rain, we begin to see a group of living organisms called Slime Molds. They are an odd group of living “things” – they are not plants nor animals nor bacteria nor amoeba. They are single celled organisms, like bacteria or amoeba, but really just a mixed group of unrelated organisms that are thought to have evolved before plants, animals and fungi. They are all thought to be consumers, preying on bacteria!

But to the nature observer or naturalist, we can only see them in two stages of their life cycle -when they mass together in a multi-celled “aggregation” of the Dog Vomit Slime Mold or when form a fruiting body (called sporangium) of the Carnival Candy Slime Mold or the Red Raspberry Slime Mold.

|

Typically seen in moist forests and most often on rotting wood that has lost its bark. Several species can be found on hardwood mulch (or plant debris) with the Dog Vomit Slime Mold being among the most commonly seen slime mold; perhaps because of the color and size. When the individual cells aggregate together, we see a bright yellow mass they will turn a darker color as it ages and can be up to about 7 inches in diameter and an inch thick. This is its spore producing stage.

Another very common one is called Wolf’s Milk and typically seen spring through fall on rotting logs. Like others, we see it when many individuals aggregate and form a small round blob from an eighth to half inch in diameter. The color varies as they age (mature) from pink to brown to black and the common name refers to a white to pink pasty fluid inside of the immature “blob” that is the fruiting body. Most often, you see many of these blobs together as in the photo.

|

|

The Red Raspberry Slime Mold is readily seen due to its color which stands on the decaying logs it typically grows on. This appears from spring through fall and is a bright red clump which can be up to six inches in diameter and fades to a brown-purple as it ages. This is one of the most widespread slime molds found throughout temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. |

Honeycomb Coral Slime Mold

Honeycomb Coral Slime Mold

What I find to be the most common slime mold in our area is called the Honeycomb Coral Slime Mold found on no bark-decaying logs in our coastal plain forests, like Dragon Run. This is usually roundish white clusters, appearing as a honeycomb, coral or icicle-like mass. This can vary from dime size to a spreading mass or masses covering a foot or more. While typically in clusters, I see it also in horizontal white strips on downed logs. Like most slime molds, it appears spring through fall with peaks following rains.

By the way, the name is derived from a “slime” like substance that the individual cells leave behind. It reminds me of the shiny slime trail of a slug or snail. Join us on one of our Dragon Run hikes and we will clue you in on these awesome but relatively unknown creatures.

Solitary Sandpiper, Tringa solitaria, by Joey Coker

Photos by Maeve Coker

Photos by Maeve Coker

When thinking of the diverse array of bird species that can be found within the Dragon Run watershed, a sandpiper is not likely to come to mind for most people. However, the Solitary Sandpiper is anomalous when compared to other shorebirds in many different ways. This medium-size shorebird is more often than not found alone, as the name implies.

They frequent the Dragon Run watershed during spring and fall migration, but only for a short period of time (May and August). While migrating through our watershed, they occur in a diverse array of habitats, as long as fresh water is present. Mudflats and salt marshes, where most other shorebirds can be found, are notably lacking from their list of preferred foraging habitats during migration.

In the Dragon Run watershed, they display an affinity for forested wetlands as well as farm fields flooded by heavy rain. The Dragon Run’s beaver dams and associated wetlands are highly preferred during migration by the Solitary Sandpiper because of the muddy edges created by dam construction. Solitary Sandpipers feed on a wide array of prey including insects, crustaceans, mollusks, small fish, and small amphibians that they hunt for from the Dragon Run’s muddy wetland margins and fallen logs that extend into the main run.

Perhaps their strangest attribute of all, though, is their nesting behavior. Solitary Sandpipers nest in trees, making them only one of two shorebird species worldwide that regularly nest off the ground. They use old songbird nests that they refurbish with fresh lining and insulation. They tend to prefer the nests of Rusty Blackbirds, Canada Jays, and American Robins. Their nesting range encompasses most of the boreal forest in Canada and into Alaska, where they prefer to nest in close proximity to small, freshwater, ponds or bogs.

Be on the lookout for these little beauties this month while you’re out in the Dragon!

Be on the lookout for these little beauties this month while you’re out in the Dragon!

May 2024

Spatterdock, Nuphar advena, by Anne Atkins

Native Americans and early colonists utilized spatterdock seeds, leaves, and flowers for food and medicine. Seeds could be popped like popcorn, ground into flour for gruel and soup thickening, or dried for long-term storage. The roots and leaves were used in traditional medicine, serving as analgesics and poultices for cuts and swelling.

Overall, spatterdock serves as a vital component of the Dragon Run ecosystem: it provides habitat, supports biodiversity, facilitates nutrient cycling, and improves water quality. Its presence underscores the interconnectedness of species within this fragile yet resilient ecosystem, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts to preserve and protect Dragon Run.

Overall, spatterdock serves as a vital component of the Dragon Run ecosystem: it provides habitat, supports biodiversity, facilitates nutrient cycling, and improves water quality. Its presence underscores the interconnectedness of species within this fragile yet resilient ecosystem, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts to preserve and protect Dragon Run.

Common Duckweed, Lemna minor, by Terry Skinner

What are those thick green mats covering the still edges of the Dragon? Is it a massive algae bloom?? It’s probably duckweed! Duckweeds are the smallest flowering plants yet discovered. They consist of one to three 1⁄8 inch long, oval, flat, green leaves that sit just at the water surface in slow-moving water bodies. A rootlet hangs down to obtain nutrients from the water instead of the soil. The flowers are so tiny that identifying them to exact species is difficult. Duckweeds grow rapidly and often reproduce by seed and asexually by offshoots which create colonies. They are quite cold-tolerant and in freezing conditions will lay dormant on the bottom until the weather warms.

There are other uses for this little wonder of a plant! Researchers use genetically modified duckweeds to synthesize insulin and other commercially valuable proteins. They also have the potential to be helpful in the development of other new biomedicines, since they are immune to animal viruses (because they are plants).

Friends of the Dragon Run love duckweed because surface-feeding ducks, like mallards, teals, and wood ducks feast on them. Reptiles and amphibians hide in the colonies while hunting or being hunted. Even dragonflies and damselflies occasionally land for a rest or to lay eggs. Duckweed is truly full of surprises.

There are other uses for this little wonder of a plant! Researchers use genetically modified duckweeds to synthesize insulin and other commercially valuable proteins. They also have the potential to be helpful in the development of other new biomedicines, since they are immune to animal viruses (because they are plants).

Friends of the Dragon Run love duckweed because surface-feeding ducks, like mallards, teals, and wood ducks feast on them. Reptiles and amphibians hide in the colonies while hunting or being hunted. Even dragonflies and damselflies occasionally land for a rest or to lay eggs. Duckweed is truly full of surprises.

April 2024

Hitchhikers on the Dragon Run by Jeff Wright

It always brings a smile to one’s face when a dragonfly or a butterfly find a kayak and hitch a ride. But the butterflies often upgrade their ticket and move from the hull of the kayak to a limb of a paddler. There is one butterfly that is the showstopper - the Zebra Swallowtail (Eurytides marcellus). It has several common names such as Kite Swallowtail and the Pawpaw Butterfly. It flies like a kite, looks like a zebra, and loves pawpaw.

The Zebra Swallowtail has thick black stripes on a white background on its wings thus the Zebra name. The tails at the end of its wings have red spots near the body. The males and females look identical. It's thin and striped wings allow it to achieve two things that help it survive – camouflage and maneuverability. It can flutter and swoop its way through the forest.

The prominent stripes make the Zebra difficult to follow as it glides and flutters through patches of sunlight and shade. It flies erratically with shallow wing beats and stays low to the ground, wetlands, and waters of the Dragon.

The Zebra Swallowtail lives in moist low woodlands near where its host plant, the PawPaw, grows. Pawpaw can be found in uplands areas of the watershed. Caterpillars feed on the pawpaw leaves, while the adults feed on nectar from flowers. The proboscis of the zebra swallowtail is much shorter than other swallowtails - such as our official Virginia State Insect the Tiger Swallowtail. Thus, the Zebra is attracted to shorter and flatter flowers rather than tube-shaped flowers.

We occasionally see the males congregate on moist soil or sand in what is called “puddling”. The male butterflies are extracting minerals and moisture from the soil which is often been enriched by poop from our many critters living within the Dragon Run Watershed.

The males patrol for females - and possibly kayaks! - flying low and back and forth along wooded areas and trails, and obviously our wonderful nooks and crannies of the Dragon Run.

Zebra Swallowtail on Common Milkweed

We occasionally see the males congregate on moist soil or sand in what is called “puddling”. The male butterflies are extracting minerals and moisture from the soil which is often been enriched by poop from our many critters living within the Dragon Run Watershed.

The males patrol for females - and possibly kayaks! - flying low and back and forth along wooded areas and trails, and obviously our wonderful nooks and crannies of the Dragon Run.

Zebra Swallowtail on Common Milkweed

Plantain Pussytoes, Antennaria plantaginifolia, by Jack Kauffman

|

Early spring is the best time to be exploring the woods of Virginia. It’s not too cold or too hot, birds and frogs are providing music to our ears, trees and shrub leaves are just appearing, and the spring ephemerals are beginning to bloom. On a walk during the first day of April, we came upon a patch of beautiful flowering plants along an old logging trail. These pussytoes were growing in a mossy area that gets partial sun and a lot of drainage. They are a perennial evergreen flowering herb and provide excellent ground cover.

A member of the aster (Asteraceae) family, the Genus name comes from the Latin word antenna because the male flowers look like antennae; and, the specific epithet (or second part of the species name) means having leaves like plantain. The plant consists of a basal rosette of hairy leaves with three to five parallel veins and an erect stem bearing the flowers. They grow just 6 to 12 inches tall and spread by runners (stolons). At this time of year, they begin to produce a tight cluster of 3 to 6 white male or female flowers on a 2 to 6 inches upright stem. The flower clusters resemble a cat’s paw (minus the claws). They last about 2 to 3 weeks and then form the individual seed pods (achenes). The flower has no apparent smell yet attracts a surprising assortment of bees and other pollinators. Since it blooms in the spring it attracts a variety of mining bees (Andrena spp.), sweat bees (Halictus spp.) and even bumble bees (Bombus spp.). It is also a host plant for the caterpillar of the American lady (Vanessa virginiensis) butterfly. |

March 2024

Northern Spicebush Spices up Our Woodlands in March By Betsy Washington

Northern Spicebush, Lindera benzoin, is one of the very earliest deciduous shrubs to bloom in our woodlands, providing fragrance, color, and nectar in late winter-early spring, when winter weary humans and wildlife need it most.

Spicebush is a member of the Laurel Family, known for such aromatic plants as Cinnamon, Bay, and Camphor. All parts of the Spicebush have a delightful spicy fragrance, from the delicate clusters of early spring flowers, to bruised leaves and bark, and even the fruit, providing an easy way to identify this shrub.

Clusters of small fragrant yellow flowers bloom on bare branches for several weeks in March, lighting up rich woods, floodplain forests, ravines, and swamp edges, as well as in drier upland forests especially those with basic soils. Although the individual flowers are small, they create a delightful show when little else is in bloom. Spicebushes are dioecious, meaning that female and male flowers occur on separate plants. In fall, Spicebush once again light up our woodlands and swamps with bright gold fall foliage which provides the perfect foil for the abundant glossy red elliptical fruit on female plants.

Spicebushes support a variety of wildlife including our earliest pollinators such as small native bees, flies, and early butterflies like the spring azure. Spicebushes are the host for at least nine species of butterflies and moths, including the stunning Spicebush, Tiger, and Palamedes Swallowtails, as well as the beautiful Promethea Silk Moth also known as the Spicebush Moth. Both game and songbirds, especially wood thrushes, relish the showy red fruit which is high in fatty lipids and especially important to migrating songbirds. Native Americans used the dried fruit pulp to make a spicy tea and to treat fevers and colds, as well as for a liniment for sores, and muscles and joints. Look for this lovely shrub this month blooming along woodland trails in Dragon Swamp.

Spicebush caterpillar - Photo by Teta Kain

Spotted Turtle, Clemmys guttata, by Adrienne Frank

The Spotted Turtle lives in the swamp of the Dragon Run. This small, delicate turtle is a favorite to find either swimming or hiding in the leaf litter. When covered in mud, it may be difficult to see the yellow spots on its black shell (carapace). The carapace is about 5 inches long when fully grown, and typically has one spot on each segment of the upper shell. Some have no spots at all.

The spots of the turtle can also be found on its head, neck, and out onto its arms. Sometimes the spots are orange, pink, or red. Females also have a yellow/orange eye (iris) and face as compared to the male dark eye and face.

The male Spotted Turtle has a thicker, longer tail compared to the female. It also has a concave underbelly (plastron). The female plastron is flat. At 8 -10 years of age, they become sexually mature and they may live as long as 25 years. Eggs are laid in early summer and incubate for about 80 days before hatching.

Spotted Turtles are aquatic omnivores. They eat both plants and animals that live primarily in shallow water. Animal food may include insect larvae, worms, crustaceans, spiders, small fish and more. These small turtles travel within limited areas; their home range is typically between 3 and 8 acres. When they do move around, they are very vulnerable to predators, especially raccoons and muskrats.

The turtles are most active early in the spring, even when the water is relatively cold. In the coldest part of the winter and the hottest part of the summer, they may slow down their bodily functions and appear dormant. They may burrow on land or in the water and have been seen to aestivate in muskrat burrows (there are many of these in the Dragon Run swamp).

Collection for the pet trade has put the Spotted Turtle on the threatened species list. It is endangered in some parts of its northern range. These turtles are particularly sensitive to pollution and toxic substances. Draining of wetlands and the fragmentation of their habitat, threaten the survival of the species.

https://herpsofnc.org/spotted-turtle/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spotted_turtle

https://srelherp.uga.edu/turtles/clegut.htm

The turtles are most active early in the spring, even when the water is relatively cold. In the coldest part of the winter and the hottest part of the summer, they may slow down their bodily functions and appear dormant. They may burrow on land or in the water and have been seen to aestivate in muskrat burrows (there are many of these in the Dragon Run swamp).

Collection for the pet trade has put the Spotted Turtle on the threatened species list. It is endangered in some parts of its northern range. These turtles are particularly sensitive to pollution and toxic substances. Draining of wetlands and the fragmentation of their habitat, threaten the survival of the species.

https://herpsofnc.org/spotted-turtle/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spotted_turtle

https://srelherp.uga.edu/turtles/clegut.htm

February 2024

Red-headed Woodpecker, Melanerpes erythrocephalus, by Sherry Rollins

This stunning medium sized woodpecker is easy to spot as it has a solid deep red hood in mature adults, a black back and snow-white body, and their wings are black at the top with large white wing patches. Males and females are marked alike and are also the same size.

Red-headed Woodpeckers are found at the edges of mature hardwood forest with clear understories where food sources such as acorns from oaks and Beech nuts are readily available. They also occur in standing timber in beaver swamps and that makes the Dragon swamp a perfect setting. In my own observations, they are often spotted on old snags which makes them easy to see.

On warm winter days, Red-headed woodpeckers may forage for insects on the ground and are also able to catch insects in flight much like a flycatcher. They also eat a variety of seeds, berries, fruits and nuts. They are known to raid other birds’ nests to eat the eggs and nestlings, and will also occasionally eat small rodents. It is the only woodpecker known to cover its stored food with wood and bark. Their stores are located in old snags, fence posts, and under shingles of a roof. When the days of winter are very cold, these birds will rely on their caches of food.

Red-headed Woodpeckers are found at the edges of mature hardwood forest with clear understories where food sources such as acorns from oaks and Beech nuts are readily available. They also occur in standing timber in beaver swamps and that makes the Dragon swamp a perfect setting. In my own observations, they are often spotted on old snags which makes them easy to see.

On warm winter days, Red-headed woodpeckers may forage for insects on the ground and are also able to catch insects in flight much like a flycatcher. They also eat a variety of seeds, berries, fruits and nuts. They are known to raid other birds’ nests to eat the eggs and nestlings, and will also occasionally eat small rodents. It is the only woodpecker known to cover its stored food with wood and bark. Their stores are located in old snags, fence posts, and under shingles of a roof. When the days of winter are very cold, these birds will rely on their caches of food.

|

Red-headed Woodpeckers are cavity nesters. The male creates a cavity in a dead tree or dead parts of a live tree. Once the female has approved the site, the two of them build the nest. Admirably, both parents incubate, feed and care for their brood. Once mated, they stay together several years.

It is the Red-headed Woodpecker's ability to excavate holes for nests that makes them and 6 other species of woodpeckers Keystone species for the Dragon. The holes created by woodpeckers are used by many other species who cannot create their own cavity (birds such as the Prothonotary Warbler and Wood Ducks). |

Sadly, populations of Red-headed Woodpeckers have been in decline due to loss of forests with nut producing trees and the dead trees needed for nesting. It truly is a magical moment to be lucky enough to make a Dragon Swamp sighting of a Red-headed Woodpecker.

Red-headed Woodpecker | Audubon Field Guide

Red-headed Woodpecker Life History, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Red-headed Woodpecker - eBird

Red-headed Woodpecker | Audubon Field Guide

Red-headed Woodpecker Life History, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Red-headed Woodpecker - eBird

White-Tailed Deer, Odocoileus virginianus, by Jack Kauffman

|

The white-tailed deer is ubiquitous east of the Rocky Mountains. It is native to all the Americas and has many subspecies. The Virginia white-tail is among the most widespread subspecies and is the only deer found in our area. We often see deer along the Dragon and it has always been a great pleasure of mine to watch them. We have photographed them using our trail cameras, crossing the Dragon, and walking along beaver dams to get a drink.

|

Deer spend most of their lives in the upland hardwood forests and edge habitats. Their diet consists mostly of woody shoots, stems, and leaves of woody plants as well as grasses, cultivated crops, nuts, berries, and wildflowers. In February, their diet consists mostly of nuts (from oak and beech trees) and buds from young trees and bushes in the understory of the forest and edge habitats and grasses in fallow fields and farmed fields. As you can see from the video, they eat mushrooms (this deer enjoying a lion’s mane mushroom) including fungi that are poisonous to humans.

|

|

There are several natural predators of white-tailed deer. Coyotes, black bear, and bobcats are still found in Virginia, though no longer in numbers to greatly affect the population. Cougars and jaguars have been exterminated from Virginia by hunting. These predators frequently pick out easily caught young or infirm deer, which is believed to improve the genetic stock of a population. Humans are however the main predator (nearly causing their extinction in the late 1800s and early 1900s). Discussions have occurred regarding the possible reintroduction of gray wolves and cougars to sections of the eastern United States, largely because of the apparent controlling effect they have through deer predation on local ecosystems. Many scavengers (including eagles and vultures) rely on deer as carrion.

https://www.yellowstonepark.com/things-to-do/wildlife/wolf-reintroduction-changes-ecosystem/ I’m sure you have been near deer and have experienced their response to your presence. They typically breathe very heavily (also called blowing) and flee. When they blow, the sound alerts other deer in the area. As they run, the flash of their white tails warns other deer. This especially serves to warn fawns when their mother is alarmed. There is no greater treat than seeing a mother walking with her fawn as shown in this photo. |

January 2024

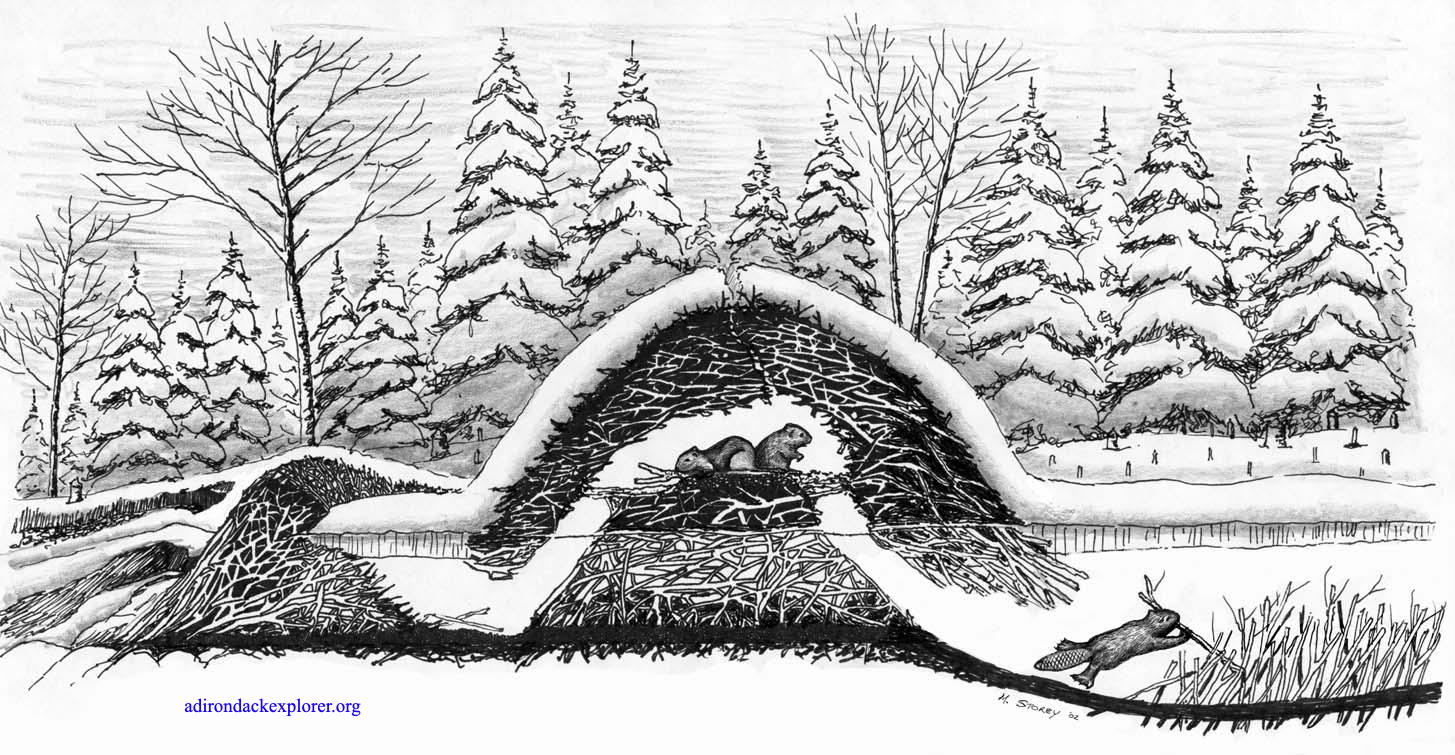

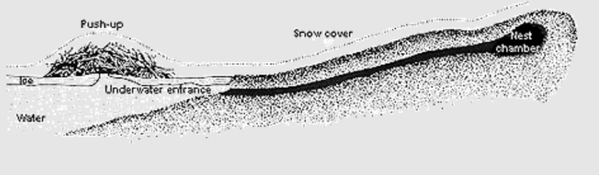

The Beaver in Winter by Kevin Howe

It’s Winter! - perfect time to highlight our premier Dragon Run keystone species, the American Beaver, (Castor canadensis). They are found far north in Alaska and Canada southward in all states though missing from southern parts of California, Arizona, and Florida.

Beavers, North American’s largest rodent (50+ lbs), do not hibernate or migrate and, depending on what latitude they are living, they may spend most of the winter inside the lodge. In Virginia, they do come out in winter but it’s variable and the behavior of our mountain beavers is likely different those in the coastal plain due to milder winters.

Beavers, North American’s largest rodent (50+ lbs), do not hibernate or migrate and, depending on what latitude they are living, they may spend most of the winter inside the lodge. In Virginia, they do come out in winter but it’s variable and the behavior of our mountain beavers is likely different those in the coastal plain due to milder winters.

|

Beavers are well adapted to winter though behavior, physiology and body structure. First and foremost, they have a double coat of fur, like dogs - a dense short underfur as well as longer, coarse outer guard hairs. Their underfur is like a wetsuit, trapping warm air against the skin. Research suggests that 20% of their time is spent combing their fur using a specialized split claw which helps keep fur waterproof and spreads oil (squalene) on the underfur to aid in waterproofing.

Some evidence shows that they eat more and increase their body fat as they prepare for winter, but they certainly eat through the winter, thanks, in part, to a large cache of wood they store in or around their lodge. Wood is their main diet in winter while plant material is the vast majority of their diet in other seasons. The outer layer of the wood, which contains the nutrients, is munched throughout the winter as needed. They are also well known to reduce activity and thereby food needs during the colder periods, though they have been observed swimming under ice and scurrying across ice in the dead of winter. |

Research inside beaver lodges shows the lodges maintain pretty stable temperatures of around 32 degrees regardless of the outside temperature. This is likely a combination of thick walls and the warm congregation of not only the family unit (5-16+ individuals) but also neighbors – turtles, muskrats, snakes. Between the placement of interlocked branches, debris, and coatings of mud on their lodge, it is well insulated. If it snows, they even get better insulation - just like a snow cave keeping them toasty.

Our North American Beavers are amazing creatures with a variety of adaptations for winter survival that have evolved over the past several million years while their habitat moved up and down in North America following the Ice Age glacial sheets.

Rusty Blackbird (Euphagus carolinus) - by Maeve Coker

How many times have you seen a blackbird and brushed it off? We are all guilty of seeing a blackbird and passing it by in search of other more beautiful, or charismatic species. This common attitude among birders, as well as researchers in the scientific community, meant we collectively went over 40 years without realizing that the Rusty Blackbird was undergoing precipitous annual declines, compounding to a 75-85% population crash since the mid-1900s.

The Rusty Blackbird is a boreal wetland breeding specialist, feeding mainly on aquatic insects. Throughout their migration and wintering habitats, they expand their diet to include nuts and terrestrial insect species. They rely on forested wetlands, agricultural fields in river floodplains, and suburban areas full of earthworms to fulfill their winter diets.

The Rusty Blackbird is a boreal wetland breeding specialist, feeding mainly on aquatic insects. Throughout their migration and wintering habitats, they expand their diet to include nuts and terrestrial insect species. They rely on forested wetlands, agricultural fields in river floodplains, and suburban areas full of earthworms to fulfill their winter diets.

|

They can be differentiated from Common Grackles and Red-winged Blackbirds by their Rusty-tipped feathers in male nonbreeding plumage, as well as overall brown plumage year-round on females. Both sexes sport a piercing yellow eye year-round. The males in the springtime will turn a beautiful glossy black, but lack the red epaulettes of the Red-winged Blackbirds, and have a thinner bill and shorter tail than the Grackles.

So why the decline? Many hypothesized compounding factors are at play, including methylmercury levels from coal ash bioaccumulating in the food chain of northeastern populations, as well as habitat loss and destruction of wetlands in the southern portion of their breeding range. Unfortunately, the archaic idea of needing to control blackbird populations in agricultural fields is still being implemented. For now, research is still being done to figure out what exactly is going on. |

Since they are largely dependent on forested wetlands and forested riparian areas for their wintering grounds in the Southeastern United States, the Dragon Run is an important wintering and migration site for them. The next time you are paddling or hiking along the Dragon, keep an eye out for them! Getting good population estimates when they aren’t breeding will help researchers since their breeding grounds are incredibly difficult to access. A healthy Dragon Run means healthy habitat for the Rusty Blackbird!

December 2023

Winter in Frog Hollow – by Kevin Howe

|

Spring Peeper

American Toad

|

Winter is a time of rest for nature. And the survival methods among various organisms is quite unique. I love frogs – they are cute, can’t hurt you, and they announce spring. They are cold-blooded (ectotherms) meaning they are the temperature in which they are living as they have no mechanisms in which to heat their body – only birds and mammals are warm blooded (endotherms) and can produce heat to warm their body. So, how do frogs survive the winter? In late Fall, as daylight shortens, and temperatures drop, frogs (and all other amphibians and reptiles) enter a state of dormancy called brumation. This state is like a long light sleep which contrasts to the longer deep sleep called hibernation that warm-blooded mammals enter in the winter - like groundhogs, bats, deer mice, and others – but not bears – ask me about the bear “hibernation” research sometime. In brumation, the organisms will get up, if the temperature rises a bit, and move around, even eat. That does not occur in mammalian hibernation. While both groups will slow breathing and metabolism down during hibernation and brumation, it is much deeper for hibernators. In our area we have 18 different species of frogs and toads, and they employ a few different strategies for winter survival. Our mostly land-living toads - Spadefoot, American, Fowler’s and Narrow-mouthed, burrow down below the frost line and “nap” out the winter; as mentioned, on warmer days, they may venture out and eat. Our tree frogs - Spring Peeper, Barking, Green and Cope’s will search out cracks in trees or logs and climb in to survive the winter – again, they may venture out on warmer days. |

Our mostly aquatic Bullfrogs, Pickeral, and Leopard Frogs, will lay on the bottom of a water body and slow their metabolism to survive. Because water is most dense at about 39 degrees Fahrenheit, there is no freeze issue if the water is deep enough. Again, if things warm up, they can swim and move around.

Our forest dwelling Wood Frog has quite an extraordinary adaptation for winter survival. As winter drops below freezing, ice crystals form in the Wood Frog’s body which causes them to accumulate urea while the liver turns glycogen into glucose (“frog antifreeze” or cryoprotectants) which then floods the body’s cells protecting the most vital organs from freezing. When warming occurs, the Wood Frog awakes. And it is our earliest breeding frog in North America. By the way, we have yet to find it in the Dragon Run Watershed but believe it should occur here although we are in the southern portion of it range.

Our forest dwelling Wood Frog has quite an extraordinary adaptation for winter survival. As winter drops below freezing, ice crystals form in the Wood Frog’s body which causes them to accumulate urea while the liver turns glycogen into glucose (“frog antifreeze” or cryoprotectants) which then floods the body’s cells protecting the most vital organs from freezing. When warming occurs, the Wood Frog awakes. And it is our earliest breeding frog in North America. By the way, we have yet to find it in the Dragon Run Watershed but believe it should occur here although we are in the southern portion of it range.

American Bullfrog Wood Frog

November 2023

Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum), by Jack Kauffman

|

Photo by James Vonesh

|

The Bald Cypress is a keystone species of the Dragon Run watershed. It is a beautiful deciduous conifer (family Cupressaceae); a tree with soft needles (feathers) that fall during the winter. In early November, the needles are a beautiful cinnamon color (transition initiated in early October). Female spherical cone-lets are maturing at this time of year, turning from green to brownish-purple before dropping from the tree. Each cone contains 2-34 seeds. Squirrels eat bald cypress seeds, but usually drop several scales with undamaged seeds. In this way, the seeds are dispersed. Cones are often carried by spring floods. Germination requires a soil saturated but not flooded for a period of one to three months. Young seedlings can grow as much as 30 inches in the first year; but will die if submerged for long periods (2-4 weeks). In the soft wet soils of the Dragon, the bald cypress forms a buttressed base and a strong, intertwined root system (knees). These features (not found when the tree is grown on dry soils) stabilize the tree. They are able to grow in these conditions to a very old age (oldest on record is in North Carolina at 2628 yrs) while other trees in the environment die at a younger age or are blown down by heavy winds. They provide a canopy that keeps the water temperature cooler, stabilize the banks to prevent erosion, and provide an environment where other plants can grow. Often maples and oaks will wrap their roots around those of the bald cypress in order to grow in the swamp or along the shore. They also provide nesting and perching locations for many of the bird species we find on the Dragon. If you haven’t been able to join us on one of our paddle trips during the fall to see the changing colors of the bald cypress or touched one of their feathers, visit the Teta Kain Nature Preserve (2994 Farley Park Road (Rt 603) Mascot) and walk the trail along the Dragon to view these magnificent giants. |

Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis), by Robin Mathews

Squirrels serve an essential role in our natural world. By “planting” numerous tree seeds and nuts (and then failing to dig them up) they help encourage diversity in our forests. They are cache-hoarders, maintaining about 1000 individual caches while burying literally 10,000 or so nuts and seeds in a given year for later consumption. They exhibit “theory of mind” thinking, in that they will “pretend” to bury an item if they are being watched to throw off a possible thief. They are known to hide behind vegetation when burying food. These are not innate behaviors. They are being devious on purpose!

The squirrel is important to our ecosystem not just because of its super seed and nut dispersal talents. They are also an important food source for coyotes, foxes, raptors, and other carnivores. However, they can be extremely frustrating to catch due to their agility when climbing and jumping from tree to tree. They are hosts for parasites such as lice, ticks, fleas, and roundworms.

The Eastern Gray Squirrel is truly an asset to the Dragon Run watershed contributing to the diversity and uniqueness of both the forest and wildlife found in the swamp.

The squirrel is important to our ecosystem not just because of its super seed and nut dispersal talents. They are also an important food source for coyotes, foxes, raptors, and other carnivores. However, they can be extremely frustrating to catch due to their agility when climbing and jumping from tree to tree. They are hosts for parasites such as lice, ticks, fleas, and roundworms.

The Eastern Gray Squirrel is truly an asset to the Dragon Run watershed contributing to the diversity and uniqueness of both the forest and wildlife found in the swamp.

October 2023

Carolina Satyr (Hermeuptychia sosybius), by Mike Grose

This little brown butterfly is often difficult to spot, unless you are specifically looking for a Carolina Satyr. Unlike larger and more colorful butterflies, the Carolina Satyr is often found flittering about, very close to the ground. Sometimes it is well hidden on leaf litter or situated in grasses.

The wingspan is only about 1.5 inches which is about half the size of an Eastern Tiger swallowtail. The unmarked upper side (dorsal) wings are a dull natural brown. While the underside (ventral) hind wing is rimmed with two dark lines and eyespots. The eyespots are believed by some to ward off predators. It is unusual to see their wings open when perching. The habitat description would include woodlands, swamps, and areas with moderate moisture. The small green caterpillars feed on grasses, while the adults feed on tree sap, animal scat and rotting fruits.

The wingspan is only about 1.5 inches which is about half the size of an Eastern Tiger swallowtail. The unmarked upper side (dorsal) wings are a dull natural brown. While the underside (ventral) hind wing is rimmed with two dark lines and eyespots. The eyespots are believed by some to ward off predators. It is unusual to see their wings open when perching. The habitat description would include woodlands, swamps, and areas with moderate moisture. The small green caterpillars feed on grasses, while the adults feed on tree sap, animal scat and rotting fruits.

|

The Carolina Satyr can reproduce three broods each year. The small green caterpillars feed on the leaves of host plants. The invasive plant, Japanese stilt grass, is said to be one of many grasses that host the Carolina satyr.

Apparently, the Dragon Run forested swamp seems to provide an acceptable habitat. In August, of this year, the first ever butterfly count was launched in the Dragon Run watershed. The count area included Middlesex, Essex, and King & Queen Counties. Thirty-seven Carolina Satyrs were recorded in the August 2023 inaugural count, which gives us a benchmark for future counts. |

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), by Maeve Coker

|

When most people hear the words “Poison Ivy”, shuddering thoughts instantly come to mind of itchy, oozing rashes that can last for weeks. But other than the irritating qualities of this vine, did you know that Poison Ivy is a dream plant for wildlife?

Poison Ivy germinates and leaves-out early in the spring. These fresh young leaves are a favored food source for both large and small mammals like deer and rabbits. Once it blooms in late spring, the flowers are covered in numerous pollinators, ranging from bees to flies to beetles. When the berries ripen in late summer and early fall, it doesn’t take long for all sorts of wildlife to find them. Because of the timing of the ripening and their hardiness through winter, Poison Ivy berries are a critical food source. Neotropical migrating birds flock to the vines as a fuel source to aid them on their journey, and those that spend the winter in our area feast on them when other food sources are scarce. Woodpeckers, warblers, vireos, titmice, chickadees, and a wide assortment of other birds utilize their energy. It also isn’t unusual for arboreal mammals, like squirrels, chipmunks, and flying squirrels, to dine on them as well. |

While we can’t ignore the rash-inducing compound urushiol that most humans have come to detest, maybe we should learn to admire the wonder and beauty of Poison Ivy from afar. There are few more exciting birding moments than watching a migrant or wintering group of birds fervently devouring the platter of berries in front of you! It is impossible to ignore the beautiful fall colors that its foliage bears, ranging from deep reds to fiery oranges! Leaving Poison Ivy to grow in an area that can be viewed from a distance is just asking for an exciting fall show of nature’s beauty. Be sure to look for it on the Dragon Run In the fall! This species thrives in disturbed sites, so the flowing water of the Dragon is always creating perfect spots for germination as the soil gets scoured frequently.

September 2023

August 2023

Water Striders, Gerridae, by Kevin Howe

Insects are quite fascinating, though chiggers, ticks and mosquitoes leave me bitten so I don’t like them much. I am particularly fascinated by Water Striders. Depending on where you grew up, you may know them as pond skaters, water skimmers, water scooters or, my favorite, Jesus Bugs, so called because of their ability to walk on water.

Water Striders are very common on the Dragon from Spring through Fall. These half inch long bugs float on the water’s surface like no other insect with their three pairs spread out to balance on the surface tension of the water. Their forelegs are short and made for rapidly grabbing prey, their long middle legs are for paddling to scoot them across the surface while their longest rear legs are used for steering and braking. In the photo you can see their legs lay on top of the water from what looks like their knee joint down to their foot (wrong terminology but gets the point across).

Water striders have evolved very well to balance and walk on water. While I often refer to them as aquatic insects, they are really not aquatic – they do not live in the water, just on top of it. And they are incapable of diving into the water.

All Water Striders are predaceous, feeding primarily on other surface invertebrates and any insects that happen to fall and float into the water. Using their piercing-sucking mouthparts, they inject dissolving enzymes and then suck up some nutrition.

Water Striders are very common on the Dragon from Spring through Fall. These half inch long bugs float on the water’s surface like no other insect with their three pairs spread out to balance on the surface tension of the water. Their forelegs are short and made for rapidly grabbing prey, their long middle legs are for paddling to scoot them across the surface while their longest rear legs are used for steering and braking. In the photo you can see their legs lay on top of the water from what looks like their knee joint down to their foot (wrong terminology but gets the point across).

Water striders have evolved very well to balance and walk on water. While I often refer to them as aquatic insects, they are really not aquatic – they do not live in the water, just on top of it. And they are incapable of diving into the water.

All Water Striders are predaceous, feeding primarily on other surface invertebrates and any insects that happen to fall and float into the water. Using their piercing-sucking mouthparts, they inject dissolving enzymes and then suck up some nutrition.

For “walking” on water, their body is perfectly balanced on their legs which along with their entire body are covered with minute hairs, over 1,000 per millimeter which not only allows them to balance on the surface tension of water, but the dense hairs repel water better than any manmade material; no water or rain will weight them down. Research has shown they can move one hundred body lengths a second (equal to almost four feet) – the equivalent of a 6-foot-tall person swimming about 9 miles a second – another reason to call them a Jesus Bug. Great water legs but totally useless on land.

In our area, water striders can overwinter on the water and be somewhat active. If the water freezes, they die but their eggs, laid on aquatic vegetation, can survive until spring in which case the young hatch out as a minute adult without a larval stage. Check them out on the Dragon or a water feature near you. A few species of Water Striders are the only insect that can live in salt water; actually, on salt water but they do live far offshore.

In our area, water striders can overwinter on the water and be somewhat active. If the water freezes, they die but their eggs, laid on aquatic vegetation, can survive until spring in which case the young hatch out as a minute adult without a larval stage. Check them out on the Dragon or a water feature near you. A few species of Water Striders are the only insect that can live in salt water; actually, on salt water but they do live far offshore.

Raccoons by Terry Skinner

Photo by Kerry Harlan

Photo by Kerry Harlan

The Raccoon, Procyon lotor, prefers forested areas near a water source (both fresh and saltwater) and den in brush piles, hollow logs, holes in trees, and even wood duck nest boxes. They shelter in dens and move to a new one every few days unless they are raising young or riding out a winter storm, when several animals may den together.

With longer hind legs than front legs it looks like raccoons run hunched over, which along with their black eye mask, gives them a sneaky appearance. They have five dexterous toes on the front legs which allow them to grasp and manipulate their favorite foods – water creatures such as frogs, clams, crayfish, fish, snails, and insects. Their ability to rotate their hind feet 180 degrees to descend a tree headfirst also allows them to catch birds and eat eggs, but they really do more foraging than hunting. Adults can weigh 15-40 pounds with urban dwellers living on human food scraps growing even larger. A raccoon can run 15 mph and fall 40 feet without injury.

With longer hind legs than front legs it looks like raccoons run hunched over, which along with their black eye mask, gives them a sneaky appearance. They have five dexterous toes on the front legs which allow them to grasp and manipulate their favorite foods – water creatures such as frogs, clams, crayfish, fish, snails, and insects. Their ability to rotate their hind feet 180 degrees to descend a tree headfirst also allows them to catch birds and eat eggs, but they really do more foraging than hunting. Adults can weigh 15-40 pounds with urban dwellers living on human food scraps growing even larger. A raccoon can run 15 mph and fall 40 feet without injury.

|

Male and female raccoons only live together very briefly to mate usually in March and April here in the Dragon Run watershed. After 65 days of gestation the female will deliver 2-4 kits which spend their first 7 weeks in the den and then begin to follow mom outside to learn to forage. Young will remain in their mother’s home territory through the winter and then move on to find their own range in the spring. Most raccoons live 2-3 years in the wild.

|

Photo by Kevin Howe

Photo by Kevin Howe

Raccoon tracks are easy to spot in the soft sand at the water’s edge, next to culvert pipe openings (which they use to cross roads), and muddy spots on human and wildlife created trails (near the new Boy Scout bridges on Swamp Trail). We enjoy watching them on our trail camera meticulously sort through the mud at water’s edge to find tasty treats.

Video: Click here.

Video: Click here.

July 2023

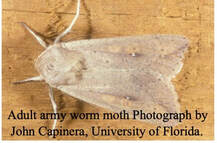

Dragonflies by Bob Diaz

Next to butterflies, dragonflies are some of the most beloved insects. Unlike butterflies and damselflies that flitter and glide through the air, dragonflies fly with purpose with their graceful, long bodies. They are on a mission either chasing food, chasing rivals, defending territory, or looking for love. They typically fly only when sunny, and when not flying they rest and keep watch. With heavy clouds or at night they perch. Extended periods of cloudiness can be life threatening as it reduces their feeding time.

In the hierarchy of insects, dragonflies are in the order Odonata that gets its name from the long teeth on its mouth parts (maxilla and labium). Dragonflies have aquatic larvae, called nymphs, that live much longer then adults, a trait know as neoteny (practiced to the extreme by Mayflies), some species will spend years (up to 5) as nymphs. Like adults, larval dragonflies are voracious predators, but much scarer looking. Mosquitos comprise a significant portion of both adult and nymph diets, along with other insect pests. Adults catch mosquitos on the wing forming their spindly legs into a basket. Nymphs thrust out their jaw (labium) to capture mosquito larvae, or any aquatic animal of an appropriate size, either by ambush or hunting. Adults are considered beneficial predators. Nymphs, while also predators, are more important as links in the food chains of fish, aquatic birds, and other large predacious insects. In addition, nymphs serve as important indicators of water quality. In Virginia, there are siting for about 140 dragonfly species with about 40 being common. Depending on the month (March to November) and sun, you should encounter several of the more common dragonflies in Dragon Run (Eastern Pondhawk, Blue Dasher, Eastern Amberwing, Springtime Darner). Resources: Great place to start is: https://www.odonatacentral.org/#/ For a list of all Virginia species of Odonata see: https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/document/vainvertlist-odonates.pdf Extra details for Virginia: Blakney, R.R. 2019. Norther Virginia Dragonflies and Damselflies: A Field Guide. ISBN 978-0578460536. 109 pp. |

Lizard tail (Saururus cernus) by Anne Atkins

Drawings by Anne Atkins

Drawings by Anne Atkins

The Latin name for lizard tail comes from the Greek word sauros which means lizard and oura which means tail. It is also known as American swamp lily and water dragon (more dragons!).

In Dragon Run, lizard tail begins blooming in May and continues to bloom through August. Tiny clusters of creamy white flowers line a stalk which almost always droops creating a lizard-tail shape. When you are close to lizard tail you will notice a citrus or sassafras smell which comes from the flowers, leaves and roots. The flowers fade to green nutlets that look like warts. In the winter, when the nutlets are fully matured, the stalks with the brown and gray nutlets, closely resemble a lizard’s mottled skin.

In the Dragon, lizard tail is robust and forms large colonies dense with rhizomes and stalks. It’s not only native to this area, but across the Eastern U.S. and is found in swamps, ponds, and areas of shallow water.

In Dragon Run, lizard tail begins blooming in May and continues to bloom through August. Tiny clusters of creamy white flowers line a stalk which almost always droops creating a lizard-tail shape. When you are close to lizard tail you will notice a citrus or sassafras smell which comes from the flowers, leaves and roots. The flowers fade to green nutlets that look like warts. In the winter, when the nutlets are fully matured, the stalks with the brown and gray nutlets, closely resemble a lizard’s mottled skin.

In the Dragon, lizard tail is robust and forms large colonies dense with rhizomes and stalks. It’s not only native to this area, but across the Eastern U.S. and is found in swamps, ponds, and areas of shallow water.

|

Lizard tail ensures its place in the ecosystem by using two methods of reproduction: seeds and rhizomes. In fact, its dense mats of rhizomes compete with other plants for resources. It is considered an emergent wetland plant meaning that the rhizomes and roots are underwater, but the stems and flowers are above water. It’s deciduous, grows rapidly, and needs little maintenance should you decide to grow some for yourself. Leaves are heart-shaped and alternate along the plant’s zig zag stem. It can grow to four feet tall and between one and two feet wide.

If all lizard tail colonies were removed from Dragon Run, the ecosystem would be significantly altered. Lizard tail provides numerous ecosystem services—food, water, and shelter for many plant and animal species. Wood ducks take cover within the lizard tail. Beavers and other animals eat the leaves. Fish, frogs, salamanders, turtles, and aquatic insects hide underwater in its stems. It’s the favorite food of turtles and attracts pollinators and beneficial insects. |

|

The thick mat of roots and rhizomes help stabilize the soil and curb erosion. In addition to beaver dams and ponds, lizard tail roots and rhizomes slow water flow through the Dragon. Plus, it’s a valuable tool for humans to use to restore and create wetlands.

Lizard tail is another example of how everything within the Dragon Run ecosystem is interconnected. Change one thing, and many things are impacted. |

Yellow-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus) by Maeve Coker

The Yellow-billed Cuckoo is a large perching bird often heard but seldom seen. They are inhabitants of dense woodlands with an abundance of cover often near water sources, including thickets along streams and low scrub along marshes. Their primal vocalizations can be heard echoing through the woods, a simple “Coo-, coo-, coo-“, or their more jarring rattling clucks.

Different from their Eurasian counterparts, Yellow-billed Cuckoo pairs build their own nests. They usually choose large shrubs about 10 feet in the air to adorn a lateral branch with their stick nests. Rather than “egg dumping” into other species’ nests for them to raise their young, the cuckoos will lay 1-5 eggs asynchronously. Each of their chicks hatch at different times, and they take less than a week to leave the nest. Chicks will spend the next few weeks of their lives crawling along limbs and branches until they can sustain flight. Nesting is often timed with the abundance (or lack thereof) of food. In years with excessive food, the cuckoos will parasitize the nests of other species, as well as other cuckoos, by laying extra eggs.

Different from their Eurasian counterparts, Yellow-billed Cuckoo pairs build their own nests. They usually choose large shrubs about 10 feet in the air to adorn a lateral branch with their stick nests. Rather than “egg dumping” into other species’ nests for them to raise their young, the cuckoos will lay 1-5 eggs asynchronously. Each of their chicks hatch at different times, and they take less than a week to leave the nest. Chicks will spend the next few weeks of their lives crawling along limbs and branches until they can sustain flight. Nesting is often timed with the abundance (or lack thereof) of food. In years with excessive food, the cuckoos will parasitize the nests of other species, as well as other cuckoos, by laying extra eggs.

The diet of the Yellow-billed Cuckoo is largely lepidopteran, especially hairy species. They consume an incredible amount of caterpillars, easily thousands in one season and even up to a hundred in one meal! They are most famous for their control of tent caterpillars and fall webworms, and they are even known to eat gypsy moth larvae. Yellow-billed Cuckoos will not turn down an opportunity though to snack on frogs, lizards, cicadas, or even small fruit and seeds. Typically in winter their diet tends to shift more plant-based compared to summer and migration seasons.

This species is a neotropical migrant, working its way south through Central America to spend the winter in South America, east of the Andes Mountains. In the eastern part of their North American range, the Yellow-billed Cuckoo population is still secure but declining. The western subspecies, however, is a candidate for review to be listed under the Endangered Species Act. Because Cuckoos have an affinity for nesting near water, the destruction of wetlands out West for agriculture has decimated their population. Fortunately, the subspecies has responded positively to habitat restoration efforts, but they still have a long way to go.

Keep an ear out for the booming call of a Yellow-billed Cuckoo the next time you’re in the Dragon, or better yet, stake out a tent caterpillar nest; you never know who may show up for a meal!

This species is a neotropical migrant, working its way south through Central America to spend the winter in South America, east of the Andes Mountains. In the eastern part of their North American range, the Yellow-billed Cuckoo population is still secure but declining. The western subspecies, however, is a candidate for review to be listed under the Endangered Species Act. Because Cuckoos have an affinity for nesting near water, the destruction of wetlands out West for agriculture has decimated their population. Fortunately, the subspecies has responded positively to habitat restoration efforts, but they still have a long way to go.

Keep an ear out for the booming call of a Yellow-billed Cuckoo the next time you’re in the Dragon, or better yet, stake out a tent caterpillar nest; you never know who may show up for a meal!

June 2023

Barred Owl (Strix varia) by Jack Kauffman

|

I love hearing the call of the barred owl. I hear it often when I arrive at the Dragon during paddle seasons or walk in the forest near my home. The sound is so recognizable “who cooks for you”. Barred owls hunt both at night and during the day, so it’s not uncommon to hear or see them in daylight. Their diet consists mostly of small mammals including: mice, squirrels, rabbits, opossums, and shrews. They also eat birds, frogs, salamanders, snakes, lizards, crayfish, fish, and insects.

Barred owls are monogamous and mate for life. Breeding season runs from December through March. To attract a mate, males “display” by swaying back and forth, raising their wings and sliding along a branch. They are mostly cavity nesters but will often use an abandoned hawk or squirrel nest. The pair will raise one brood each year. |

Beginning in March, the female lays two or three white eggs, which hatch in 28 to 33 days. The female will stay with the young at first while the male hunts and provides food for its mate and young. Young barred owls leave the nest four to five weeks after hatching and can fly in six weeks. On May 20th, we were paddling the Dragon around 6pm and heard an odd sound and rustling in the tree. What we saw was an adult barred owl dropping off food for its two very large babies. The parent left and the two young stared down at us from their perch on a bald cypress branch. They bobbed their heads and made screeching sounds for a long time before we continued on our way. Here is an example of the sounds the young made. Sometimes the conversation between two barred owls can get rather interesting. I’ve heard something like this in the woods at our house.

These owls favor mostly dense and thick woods with only scattered clearings, especially in low-lying and swampy areas. They will live in one location for their whole life. Still widespread and common, their numbers have declined in parts of the south with loss of swamp habitat. Just one more good reason to save the Dragon!!

Bee-Dazzled by Pickerelweed by Betsy Washington

Photo by Betsy Washington

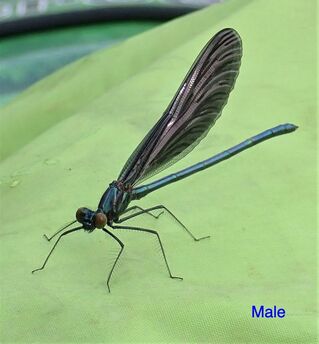

Ebony Jewelwing Damselfly by Kevin Howe

There is a “tale” that Dragon Run is named because of all the Dragonflies that are seen in the summer-fall along Dragon Run – that just might be true; then again, maybe just a tale but a plausible one.

Indeed, Dragonflies are quite abundant here in summer along with their little cousin, the Damselflies. Dragonflies are typically larger than Damselflies and they are easily distinguished from each other by the way they hold their wings at rest – Dragonflies hold their wings open and perpendicular to their body while the smaller Damselflies hold their wings closed and over their body. Both are voracious carnivores, mostly on other insects and can be cannibalistic. These predaceous insects belong to an insect group (Order) named Odonata.

On every non-winter visit to Dragon Run waters, there is one Damselfly that you are guaranteed to see - the Ebony Jewelwing (Calopteryx maculate). Active from April to around October, this Damselfly is super abundant and “friendly”, if you can call an insect that. Not unusual to see one or more flying around and even landing on your kayak or you!

Indeed, Dragonflies are quite abundant here in summer along with their little cousin, the Damselflies. Dragonflies are typically larger than Damselflies and they are easily distinguished from each other by the way they hold their wings at rest – Dragonflies hold their wings open and perpendicular to their body while the smaller Damselflies hold their wings closed and over their body. Both are voracious carnivores, mostly on other insects and can be cannibalistic. These predaceous insects belong to an insect group (Order) named Odonata.

On every non-winter visit to Dragon Run waters, there is one Damselfly that you are guaranteed to see - the Ebony Jewelwing (Calopteryx maculate). Active from April to around October, this Damselfly is super abundant and “friendly”, if you can call an insect that. Not unusual to see one or more flying around and even landing on your kayak or you!

|

The Ebony Jewelwing is rather small, about two to three inches long and is found in much of the Eastern North America. It is a brilliant metallic green which often appears blue depending upon the light and, like all Dragonflies and Damselflies, they are mostly seen around freshwater. The eggs must be laid in water or on material close to water (rocks, vegetation, etc.) and the female will lay several hundred eggs in an area protected by the male. The eggs hatch into carnivorous crawling larva, called naiads, live in the water for up to a year after which they will crawl up something (plant, stick) out of the water and transform into the flying adult. The adult lives only long enough to breed which is about two-three weeks. Interesting note, the female differs from the male by possessing a white mark on the upper rear portion of the forewings.

Virginia has over 200 species of Dragonflies and Damselflies with about 76 species identified as a “Species of Greatest Conservation Need” by Virginia’s Division of Natural Heritage. As with most of our native flora and fauna, the loss of quality habitat is the most significant threat. In the Coastal Plain, about 41 species of Damselflies have the potential to occur although the number that have been verified is much less. But the high natural quality of Dragon Run certainly is a haven for all of our Dragonflies and Damselflies and more study of these fascinating creatures is needed. I am sure your Dragon Run guides will be pointing out the Ebony Jewelwing Damselfly on your next kayak trip down the Dragon – they are stunning! |

Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) by Robin Mathews

|

One of the most exciting moments each spring happens when you spot your first Eastern Tiger Swallowtail. I happened to be walking one of the trails on the Big Island property in March when I spotted my first of 2023. These butterflies are most commonly found in deciduous woodlands and in fields where there are flowers for nectar. The Tiger swallowtail is easily identified. It is one of our largest butterflies. The bright yellow and black “tiger” stripes are distinctive and can be seen from far away. The undersides of the hindwings have bright blue spots around the margins. Some female tiger swallowtails, especially in the southern part of its range, are a dark color. One theory is that this makes the female resemble a Pipevine swallowtail which gets protection from the toxic pipevine sap that its caterpillar eats. Female tigers lay eggs on the leaves of various host plants including tulip poplars and black cherry trees. In the southeast there are often 3 broods. The last brood of the season overwinters as chrysalises on tree trunks or in the leaf litter. As the caterpillar matures, it becomes bright green with eyespots on either side of its head. The caterpillars have an organ called an osmeterium, which is an orange-red forked gland that the caterpillar can pop out if threatened. It looks a lot like a snake's tongue and is bad smelling. This may have evolved to help keep predators away. One interesting phenomenon associated mostly with male Tiger swallowtail is ”puddling.” They can be seen in groups on moist dirt, scat, or shallow puddles, drinking the salts and minerals. I had the good fortune to see it twice while paddling on the Dragon this spring. The next time you walk where there are wildflowers, take your camera. The Eastern Tiger Swallowtail is one of the most abundant and easily spotted butterflies in our area. You might just get a beautiful photo of one of these amazing insects as it drinks nectar and pollinates the flower. |

May 2023

Turtles by Kevin Howe

|

Eastern Painted Turtle, Chrysemys picta

Woodland Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina carolina

|

Turtles are a fascinating group of reptiles which we see with some regularity on our hikes or kayak cruises in and around Dragon Run. Somewhat prehistoric looking, the group is easily recognized by just about anyone over the age of three.

We have seven different species in and around the Dragon Run watershed – one species, the Woodland Box Turtle is entirely terrestrial while six other species prowl the waters of Dragon Run with a few of them, spending some time out of the water (mud turtles). All 356 species of turtles worldwide lay their eggs on land with one exception, an Australian Snake-headed Turtle which will lay the eggs in a wetland, but the wetland (Billabong) dries up before the eggs hatch. On our hikes, we occasionally see a Box Turtle and they are easily recognized as they crawl at a snail’s pace along woodland floor. Their dark brown shell is patterned with orange and yellow markings which camouflage it amazingly well against the forest floor; many a time I have almost stepped on them only recognizing them at the last instant. |

|

The most numerous aquatic species we see are the Eastern Painted Turtle followed by the Southeastern Mud Turtle and the Red-bellied Cooter. On one of our early morning spring hikes, we were absolutely amazed to find a female Southeastern Mud Turtle laying eggs, a rare and lucky sighting indeed! Our most usual encounters happen when we are on the water. We usually see them in one of three ways – sunning themselves on a log, floating just beneath the surface of the water with their snouts sticking out of the water or while they are just floating along mostly submerged. We most frequently we see them sunning themselves on a log but if you have sharp observation skills, you may spot the snout more often.

|

Snapping Turtle floating on the water for a breath

|

The month of May is often peak time to see turtles as they are just coming out of their winter hibernation state (called brumation in reptiles, hibernation in mammals) and being cold blooded, they get out of the water to absorb the springtime heat of the sun. Although we see them with regularity, they are skittish and are easily startled and quickly slide into the water. So often, a turtle sighting is a fleeting but exciting observation.

Red-bellied Cooters both enjoying the sun’s warmth

Beaver by Carol Kauffman

|

Our FODR volunteers have been busy leading guests on trips down Dragon Run. Another species that has been busy is the Beaver, Castor canadensis, the largest rodent in North America (typically 35 to 70 pounds and three to four feet in length.). Spring is the time when females give birth. The kits stay close to their mother during their first 6 weeks, remain with their parents for two years, and help raise the next year’s offspring. Kits are preyed upon by fox, otters, mink, eagles, owls, and large fish. The lodge, built of sticks, mud, and plant matter, is home to this multi-generational family and can house other species like muskrat, frogs and turtles. The beavers’ lodge entrance is underwater to provide safety from predators. Their signature flat tail is slapped on the water to signal danger. It serves as a rudder for swimming and for balance when on land. Fat is stored in the tail for when food supply is low.

The beaver is a keystone species; a species that has a disproportionately large impact on its environment, holds ecosystems together, and supports biodiversity. The pools the beaver make from building dams, create new habitat for many other species. Fish, ducks, frogs, turtles, and aquatic plants utilize the pools that are created by the beaver dams. On our paddles we often see eagles, kingfishers, and herons feeding in these pools, and we have seen signs of raccoons who leave their prints along the banks. |

|

Some consider the beaver an engineer because of their ability to build sturdy lodges and dams; but I like to think of them as farmers because the pools they create become great habitat for the plants the beaver uses for food and for building. Beavers are nocturnal, but are occasionally active during the day. They do not hibernate, but are less active during winter, spending most of their time in the lodge or den. It’s rare, but occasionally we see a beaver on our paddle trips. A special treat is to be sprayed by the water that splashes when one slaps his tail next to your boat.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) by Adrienne Frank

In the spring, plants such as the Mayapple emerge and flower on the forest floor of the Dragon Run Watershed. These plants die back, and are not visible late in the summer, fall, or winter months.

Mayapples grow in colonies, covering an area with their umbrella-like form. The plants spread by rhizomes under the ground, sometimes covering large areas. They like forest floors with rich, moist soil and are in bloom March through May throughout Virginia.

Mayapple leaves are deeply lobed at the top of a stem. The nodding white flower and yellowish fruit hang below the leaves and are concealed from view. The egg-shaped fruit can be 2 inches long. When ripe, the little apples are edible and eaten by raccoons, box turtles, opossums, and skunks.

Mayapples grow in colonies, covering an area with their umbrella-like form. The plants spread by rhizomes under the ground, sometimes covering large areas. They like forest floors with rich, moist soil and are in bloom March through May throughout Virginia.

Mayapple leaves are deeply lobed at the top of a stem. The nodding white flower and yellowish fruit hang below the leaves and are concealed from view. The egg-shaped fruit can be 2 inches long. When ripe, the little apples are edible and eaten by raccoons, box turtles, opossums, and skunks.

|

Leaves and stems of Mayapples are toxic, containing podophyllotoxin which is an ingredient in some prescription drugs (including anti-cancer agents and laxative). Native Americans used the plant as an insecticide and the roots were used as worm expellants, for jaundice, constipation, hepatitis, fevers and syphilis.

The Virginia Native Plant Society describes the historical names for the plant, which include: the Cherokee name means “it wears a hat”; the Osage Indian name “it pains the bowels”; the English, thought this plant resembled |

the European mandrake plant, and called it American Mandrake; a French botanist named the genus, Anapodophyllum, meaning “duck’s foot leaf”. Over the years, Mayapple was placed in several families of plants and now, after DNA analysis, it is placed in the Barberry family (Berberidaceae).

https://vnps.org/princewilliamwildflowersociety/botanizing-with-marion/history-of-the-naming-of-the-mayapple/

Hamilton, H. & Hall, G. (2013). Wildflowers & Grasses of Virginia’s Coastal Plain. Botanical Research Institute of Texas Press.

https://vnps.org/princewilliamwildflowersociety/botanizing-with-marion/history-of-the-naming-of-the-mayapple/

Hamilton, H. & Hall, G. (2013). Wildflowers & Grasses of Virginia’s Coastal Plain. Botanical Research Institute of Texas Press.

April 2023